Written by: Armando Armenta

The emergence of Javier Milei as the favorite in Argentina’s presidential race shocked onlookers and ignited debate about the role of central banks in emerging economies. The run-up to the October presidential elections promises to feature much discussion about potential uses and misuses of monetary policy—and a sovereign currency.

Calling Central Banks into Question

Milei, who led all candidates in Argentina’s recent primary election, has vowed to eliminate the country’s central bank and replace the Argentine peso with the US dollar, in a transition that could last from 12 to 24 months. In a recent interview, he said, “central banks can be divided into four categories: the bad ones, like the Federal Reserve; the very bad ones, like those in Latin America; the horribly bad ones; and the central bank of Argentina.”

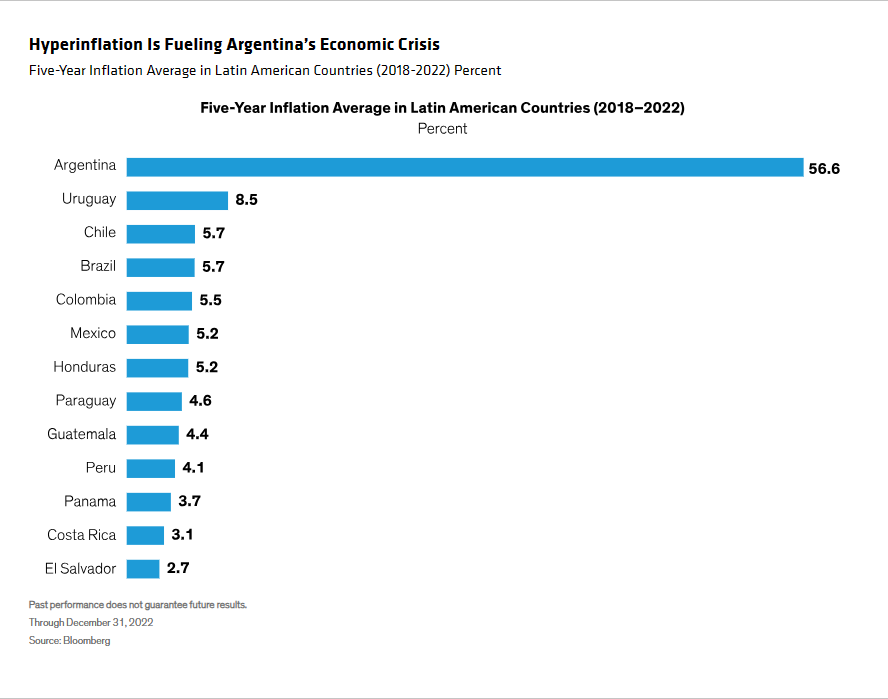

With inflation in Argentina running above 100% for the first time in decades, Milei’s focus seems squarely on the policy mistakes that have ignited persistently high inflation (Display) and exacerbated the country’s economic crisis.

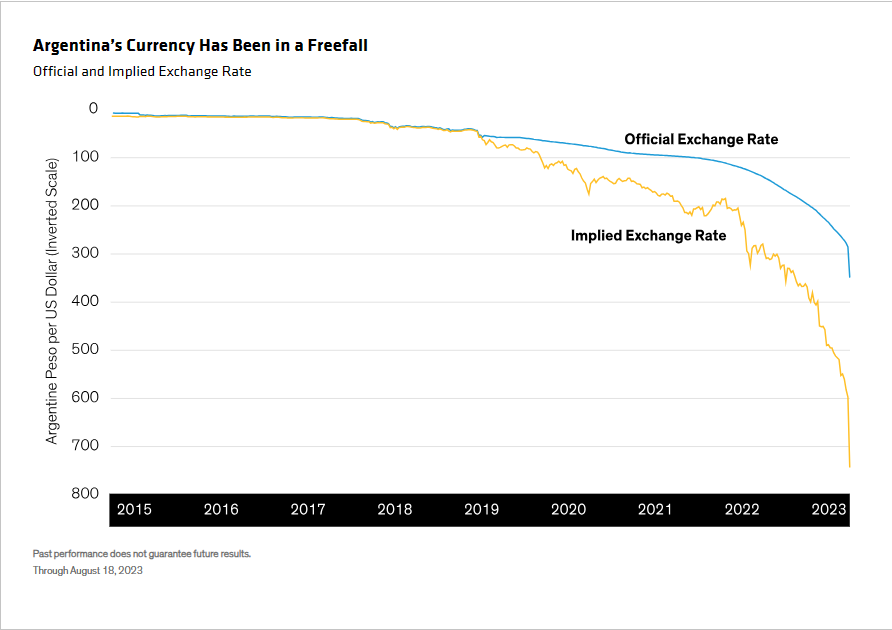

On the other hand, well-managed currencies have the potential to help reduce economic fluctuations and the negative impacts on employment and income. The Argentine peso, however, has been spiraling downward over the past few years (Display), with the drop accelerating under the current administration.

Following in the Footsteps of Panama and Others?

If Milei is elected and delivers on his campaign pledges, Argentina would become the fourth Latin American country to adopt the dollar as its official currency, following Panama, El Salvador and Ecuador. While those three countries have been able to reduce inflation to persistent single-digit figures, only Panama’s case can be considered successful, in our view.

By dollarizing, both Ecuador and El Salvador have surrendered an important countercyclical tool—one that enables them to devalue their nominal exchange rate in the face of both internal and external economic fluctuations. The loss of this capability exacts high costs in terms of economic growth, fiscal and external revenue, and emigration of residents during times of crisis.

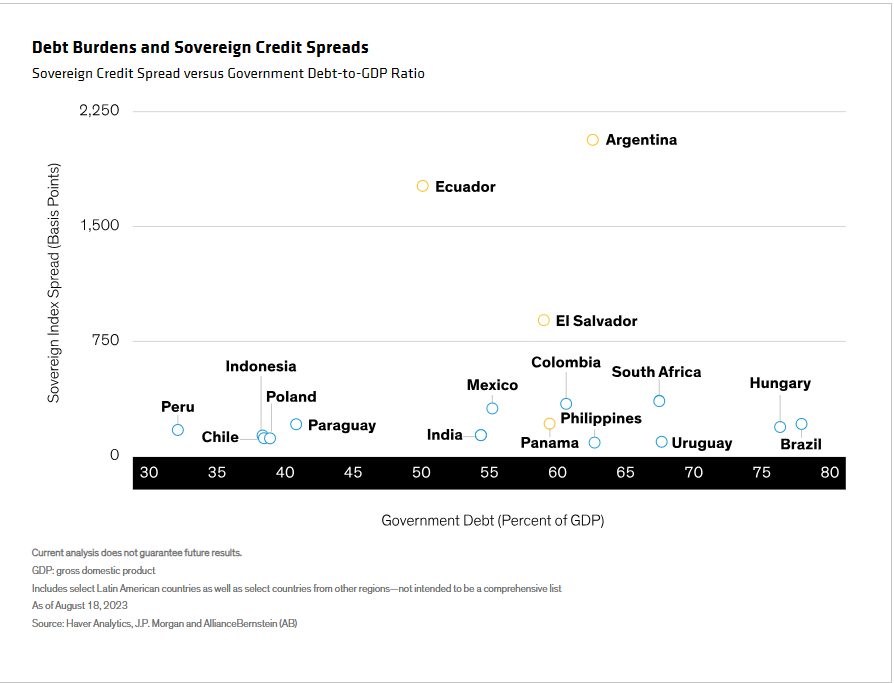

Both countries have recently imperiled their capacity to repay sovereign external debt (Display). Panama, predominantly an exporter of financial services and global maritime transportation through its canal, faces lower volatility in its external and fiscal accounts, so the stability provided by the dollar outweighs the costs of sacrificing its monetary sovereignty.

Should Argentina’s Course Include Dollarization?

Is dollarization and eliminating monetary policy the best solution for Argentina, where inflation forecasts for 2023 hover around 160%?

The country’s economy relies heavily on exports of agro-industrial and energy products, both for foreign trade and government revenues. Prices on these goods fluctuate a lot—from the impact of basic commodity prices and, as in 2023, droughts. The core of Argentina’s recurring crises is that both imports (intermediate goods for manufacturing and services) on the external side and the expenditures of a benevolent welfare state are much less volatile than their respective incomes.

The government’s economic policy mistake has been too much use of both internal and external debt, as well as financing the fiscal deficit through the central bank, seeking to bridge the gap between income and expenses. We think resolving this problem would be a less painful solution than abandoning the Argentine peso altogether. However, the evidence does support Milei’s argument that Argentinians have been unable to reach a solution to this point. As a result, the more radical option is gaining support.

So, Argentina currently stands at a crossroads. A wrong combination of monetary and fiscal policy has exacerbated its economic crisis. Monetary policy offers a potential solution but has been unable to deliver to this point. Dollarization offers a possible solution but also brings risk—and the decision is most likely irreversible. If Milei is elected as Argentina’s next president in October, we’ll learn which path the country will follow.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. Views are subject to revision over time.